Cynthia Ruchti shares from her heart about All My Belongings

|

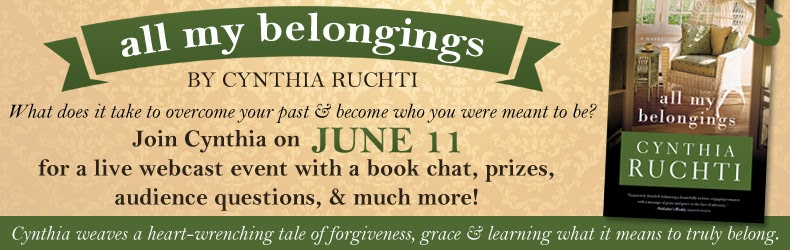

The webcast will be hosted on Ruchti’s Facebook page, as well as the Litfuse Publicity Group website for readers without a Facebook account. Leading up to the

webcast, readers can RSVP for the event and sign up to receive an email reminder. From May 22 – June

10, fans can also enter the contest for the Grand Prize VISA cash card via the

author’s Facebook page or the blog tour landing

page.

An interview with Cynthia Ruchti,

Author of All My

Belongings

Some people are raised by doting parents in a loving home where they

have a safe place to grow, to belong. Others come from homes broken by an

absentee parent, hurtful words, regrets, promises not kept or a myriad of other

sins. In All My Belongings (Abingdon Press/May 6, 2014/ISBN: 978-1426749728/$14.99), author Cynthia Ruchti tells the

story of a young woman who feels out of place within her own family and must

learn to live in the shadow of guilt and shame that haunts her as a result of

her father’s crimes. A new life and a new identity can’t free her from a past

that refuses to go away.

Q: Your books — both fiction and non-fiction — tend to

have a strong personal tie to them. What from your own personal experiences do

you bring to All My Belongings?

The heart of the

author comes out in everything he or she writes. My books are a blend of

emotions or experiences I’ve known and a heightened empathy for friends and

family who’ve walked these paths. From those very real challenges, I draw on

imagination to create stories that aren’t afraid to tackle tough subjects, but

with what I hope is an embracing and bracing tenderness and compassion. That’s

definitely true with All My Belongings.

While I didn’t have the main character’s embarrassment about her parents and

where/who she came from, I’ve known others whose families make their lives

miserable.

Where I do connect

deeply with the story is caregiving for someone in her final days of life. My

mother was what we call “actively dying” for four years and entered a residence

hospice for what we all assumed were the final two or three days of her life. She

endured another nine months of the dying process before she went Home. All she

craved was my time. Her need seemed so familiar. When I was a child, she worked

nights and slept days. It took a toll on her, on all of us. Her devotion to

nursing was strong, and she was good at it. I didn’t always understand or

appreciate her exhaustion or why she couldn’t attend a school function or have

the kind of time for me I hoped for. I knew she loved me, but I craved her

presence. Then, in the end, that’s all she wanted from me. I know I’m not alone

in having had to work through and set aside my past longings in order to give

her what her heart needed. Celebrating the tender moments and loving through

the ugliness of the natural processes of dying made an indelible impression on

me. Dying is an inescapable part of living. Figuring out how to do it well,

whether the person leaving the earth or the one left behind, is an intricate

dance that is beautiful when mastered, but clumsy when the lessons are ignored.

Q: The lead character, Becca, struggles with feeling like

she’s never really belonged anywhere. Isn’t that something we all deal with at

some time or another? Is there anything that makes Becca’s situation different

than most?

Women make up the

majority of my readership. I have a theory that we women never completely leave

junior high. We weave in and out of experiences that challenge our sense of

belonging. Sometimes we feel disenfranchised, even in a marriage or with our

nuclear family. Work situations can throw us into another cauldron of confusion

about where we fit. As readers take Becca’s journey with her, they’ll find that

our place to belong doesn’t always look like we thought it would. Our

assumptions get trumped by the surprises into which we feel our soul settling. “Ahhh.

This is it. This is where I belong.”

Sometimes as we gain

from what we survive, we discover what we were seeking was ours all along, like

Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz. Our life

strips away the distractions so we see the One who created a belonging place

for us that can’t be taken away by how we feel or what happens to us or where

we came from.

We’re all misfits, in

some way — at church, at home, in our neighborhood, among our friends, in our

extended family. There’s something about us that creates a sense of

restlessness on some level, even when life is perking along. We find ways to

adjust around our “misfitness.” The word “achieve” is interesting applied to

belonging. I think in many ways it isn’t a pursuit as much as it is a

discovery. Discovering where we fit in God’s scheme makes the other puzzle

pieces fit for all of us.

Q: Have you ever had to separate yourself from a family

member or friend because of something that happened in the past?

Q: Have you ever had to separate yourself from a family

member or friend because of something that happened in the past?

I’ve known people who

have had to, but I haven’t personally been in that position. I come from an

exceptional family history. Throughout the years I’ve listened to the heartbreaking

stories of others who were abandoned, ignored or neglected, and whose parents

acted as if they had no children even though they did.

Q: There are a number of ways you could have written

about a young woman trying to escape the sins of her father. What made you

choose the crime of euthanasia?

The numbers of novels

dealing with physical or sexual abuse are many. But sometimes what makes us

ashamed of our past isn’t related to that kind of abuse or takes abuse to yet

another despicable level. I wanted the story to explore what it‘s like to have a

parent’s reputation taint not just a daughter’s life, but the community’s. I

needed the character to wrestle with something different from other books on

the market, and yet the emotions are in many ways the same as any kind of

barrier between the heart of a child and the heart of a parent.

In this case, her

father’s acts had a more far-reaching effect on others, not only in what he

did, but the attention on the trial and the press, all of which made it more

difficult to escape the spotlight. Her father’s choices went against her own

convictions, but how would she respond when those convictions were put to the

ultimate test?

Q: For most Christians euthanasia is a very black-and-white

issue. Do you personally feel there is ever an area of gray?

We assume we have it

all figured out. There’s criminal euthanasia — for personal gain, either

financially or for some other twisted reason. There’s involuntary euthanasia — where

the perpetrator believes he or she is doing the right thing in ending a tortured

life, but against the wishes of the person killed. Then there’s voluntary

euthanasia — when the patient is involved in the decision-making.

We may have our feet

planted firmly on the side that none of the above is acceptable. I didn’t

include this subplot to present an essay on the evils of euthanasia, but to spark

conversation about why we believe the way we do. For me, it created a framework

against which I could examine what else is involved in decisions like these.

What kind of pain presses people to even consider euthanasia? And how can we

condemn those who wrestle with the issue, especially those who have sat at the

bedside of a terminal loved one in extreme, relentless distress?

Personally, I believe

our default option has to be letting God decide the length of our days. I have

witnessed such indescribable beauty, even in the hard days at the end of

someone’s life, and I wouldn’t want to grieve over the tenderness missed in

cutting that time short.

Q: Not only did Becca feel guilt by association due to

her father’s actions, but bore the guilt of reporting his crimes to

authorities. What are some ways we can deal with the various kinds of guilt we

bear in our lives?

Guilt isn’t always a

bad thing. Sometimes it serves as a warning to us that prevents bad choices in

the future. Sometimes it presses us to ask forgiveness and re-establish a

broken relationship, or make restitution for a wrong we’ve done. That’s a

sorrow (or a guilt) that leads to repentance, as the Bible says.

But when guilt is

unwarranted or we’re bearing guilt vicariously for someone else’s deeds, then

we are carrying around a weight we weren’t meant to carry, and it threatens to

bend our emotional spines into permanent disfigurement. Sorting through

reasonable versus unreasonable guilt is a first step.

Guilt can become a

label. Not only do we have to remove the label intentionally, we need to ensure

it doesn’t become a tattoo. Guilt can serve a purpose, but after that purpose

is served, there’s no option other than to discard it.

The words come

easily. The process can be emotionally taxing.

Q: All My

Belongings addresses caregiving and the responsibility of spouses and

children. Do you believe caregiving is something inherent or something we

learn? Does how we are parented as children affect how compassionate we are

toward others?

Personality traits

affect our caregiving abilities. Some seem gifted for it. Others are as awkward

in caregiving as a kangaroo on stilts. No matter where we are on the spectrum,

we can learn a more graceful and grace-filled caregiving. Insecurities can keep

us from being a natural caregiver, but we can grow in the practice as we

observe someone who is elegant at it. Even if our first attempts are clumsy, we

can catch onto the rhythm of it, if our heart’s in the right place and we’re

humble students of the process.

Q: In All My Belongings, the strongest victories came from situations

that look completely bleak and hopeless, yet the characters press on. How is

that a reflection of life outside the pages of a novel?

The

most memorable moments and the seasons with the strongest impact on my own

character have been the ones that challenged me and called for a depth of

courage I didn’t know I had. Losing someone I loved. Dealing with a traumatic

diagnosis. Knee-rattling concern over a loved one’s choices. Upheavals in

routine.

Some of the characters in All My Belongings adopt the phrase “guacamole!”

to underscore the truth that some things in life are even better after they’re

pulverized. Tracing back through the years, we can probably all point to times

when we discovered a depth of meaning behind that statement. Life can mash us

or tenderize us, depending on our response to its challenges.

Q: How does forgiveness

impact parent-child relationships even in adulthood?

Sometimes we outgrow or overcome the resentments, embarrassments,

and hurts we experience in childhood . . . even those natural to the best of

homes. But unforgiveness between parents and their children can utterly poison

their adult relationships. What could be more heartbreaking than parents and

grown kids unable to connect, harboring old grudges or vindictiveness over old

sins? A friend of mine suffered at the hand of an abusive step-father. Because

she determined to be generous with forgiveness, throughout the years his heart

softened. Those in-between years weren't easy for her, but by God's grace, she

kept a firm grip on her commitment to forgive and love whether he deserved it

or not. The relationship they have now is the kind of step-father/step-daughter

bond others wish they could know. It's almost become a comedy routine to think

of holidays and other family gatherings and assume the dysfunctions will

create the stories told after the fact. Forgiveness can change those stories to

something soul-satisfying and God-pleasing.

Q: What is the one spiritual lesson you hope readers will

walk away with after the last chapter of All

My Belongings?

Finding

where we belong is less about a place or a reputable heritage and more about a

faith that forms the foundation of all other belonging.

Comments