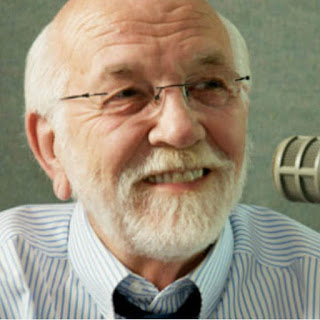

Telling the Truth, Even When it’s Unpopular

Author of Talk the Walk: How to Be

Right without Being Insufferable

The Christian faith is true, and while we may be right on issues of salvation and theology, we may miss the less articulated truths of humility, love, and forgiveness. We live in a culture that is increasingly hostile to Christians and their faith. Talk the Walk (New Growth Press) by pastor and author Steve Brown unpacks the call to “go out into the world” and share faith by being truthful and winsome. By helping men and women love others out of a deeper love in Christ—the one who first loved us—Talk the Walk helps Christians present the gospel clearly and with compassion.

Brown

encourages readers to:

- Take a step back and look at others’ perceptions.

- Explore the tools necessary to accomplish an attitude change of confidence and humility, repentance and truth.

- Share the message of Christ without distorting it.

- Speak confidently without being cold.

- By operating out of humble gratitude for the gospel, begin to talk the walk of Christian faith, reflecting the love and truth of Jesus.

This

attitude-altering book invites Christians to cultivate boldness and humility in

communicating gospel truth. By uncovering self-righteousness and spiritual

arrogance, Talk the Walk shatters

stereotypes and helps believers consider how they present the good news without

watering it down.

Q: Why can’t we all agree on truth?

When one is

referencing the disagreement on truth claims between Christians and

unbelievers, it has to do with how one sees truth. A meta-narrative is a

narrative at the heart of all that is, explaining all that is. The Christian

faith is a stable (and true) meta-narrative, and we live in a culture that

rejects all meta-narratives. In other words, there isn’t any such thing. If one

decides to be “good,” for instance, one must ask, “Why is good, good?” If

there’s no meta-narrative (no God), then good is what one decides is good and everything

is up for grabs.

But then there

are a lot of places where Christians disagree among themselves about certain

truths. In this book, I’ve tried to avoid those areas of disagreement and

center in on what C. S. Lewis called mere

Christianity (a term he got from Richard Baxter, a seventeenth-century

English Puritan church leader and theologian), referring to the basics of the Christian faith as expressed in,

for instance, the Apostles’ Creed. The Evangelical Presbyterian motto is quite

good: “In Essentials, Unity. In Non-Essentials, Liberty. In All Things,

Charity.” That works for me.

Q: What do you mean when you say, “We are right and they

are wrong”? Why is it dangerous to be right?

I mean that we are right and they are wrong . . . but certainly not that we are right about

everything and they are wrong about everything. In fact, they may be more right

than we are, and we could be more wrong than they are. But in terms of the

eternal verities of the Christian faith (again, mere Christianity), we really

are right and those who disagree are wrong. If I didn’t believe that, I would

not have written this book, and I would have gone into vinyl repair where it

didn’t matter. Not only that, if Christopher Hitchens in his book God Is Not Great didn’t believe he was

right and Christians wrong, he would not have written his book either. The

difference is I really am right and he really is wrong, and now he knows it.

That’s not arrogance; it’s the nature of truth. Aristotle’s principle of

non-contradiction—that contradictory propositions cannot both be true—is

helpful to remember.

The Christian

faith is either right or wrong. If it’s right, it’s the best news the world has

ever heard. If it’s wrong, it doesn’t matter. We don’t say that very often

because it gives offense. But it needs to be remembered and said often.

When Barry Goldwater ran for president, he

had the unfortunate habit of being controversial in the wrong places. For

instance, he would sometimes campaign in Florida and speak against Social

Security and in Tennessee speak against the TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority).

One of Goldwater’s senator friends said to him, “Barry, I know you have to walk

through the field where the bull resides, but you don’t have to wave a red flag

in his face every time you do.” That would be good advice for Christians. We

don’t have to die on every hill, fight in every battle, and correct every

error. Frankly, we’re not that good or wise. Silence really is golden,

especially when words are so often used to manipulate and demean others, to

gain power, or to protect “our castle.” Sometimes silence is its own witness.

That doesn’t mean Christians should not speak

truth. It does mean, however, some truths are more important than others.

Christians should pick their battles very carefully when talking to

unbelievers, and those battles should rarely be battles over partisan politics,

social mores or minor theological propositions. Frankly, unbelievers don’t care

about how many angels can stand on the head of a pin or which political

position is anointed by God. Forgiveness, love and redemption should be shouted

from the rooftops, but some subjects should be relegated to the basement.

Q: How can we confidently speak the truth without coming

off as arrogant or self-righteous?

I hate to keep

bringing up the subject, but truth isn’t the problem. It’s the speaker of that

truth. One time, the late Swiss Christian physician/psychiatrist Paul Tournier

was asked if he knew Christians who didn’t live their faith. “Of course I do,”

he replied. “Me.” The way one speaks truth without coming off as arrogant or

self-righteous is not to be arrogant and self-righteous. If the Bible is true

(and I have good reasons to believe it is), when we bring our witness to the

world, get baptized or join the church, we’re making a public announcement

about our sin, neediness and lostness. That reality doesn’t dissipate on the

good side of our witness, our baptism or our church membership.

A dangerous

prayer is the Psalmist’s prayer (Psalm 139), “Search me, O God, and know my

heart . . . see if there be any grievous way in me.” That is a prayer

God almost always answers, and it should be prayed before we ever try to speak

truth to those who don’t want to hear.

There’s an old

story of a young man applying for a job. When the man entered the owner’s

office, he was working on some papers and said, “Take a chair. I’ll be with you

in a minute.” “Sir,” the young man said, “I’m the son of Senator Smith.”

“Then,” the boss said, “take two chairs.”

Christians hardly

ever take two chairs. The Scripture simply doesn’t allow it.

Q: We hear the phrase “speak the truth in love” often,

but are there things we are misunderstanding about love that result in not

speaking the truth well?

I wrote a chapter

on love for this book, but it turned out to be a lot different than I thought.

I found out I didn’t have the foggiest idea of what love was. And you don’t

either. Passages such as 1 Corinthians 13 are “checklists” describing what love

does, not what it is. I know about the different Greek words for love, but that

doesn’t help either. As a matter of fact, love happens. When Supreme Court

Justice Potter Stewart described obscenity

as something he couldn’t define but knew when he saw it, he could have been

describing love. Love can’t be fixed, controlled, manufactured or earned. It

comes from being loved unconditionally, deeply and without reservation

(something you know when it happens), and it’s the key to our witness to

unbelievers. One can’t love until one has been loved and then only to the

degree to which one has been loved. We are called to practice love at church

(no mean thing); and then, when we get that right, to go out into an unloving

world and become instruments whereby the world experiences it. They will know

it too, when they experience it.

I think we

sometimes talk about love too much. We preach too many sermons, write too many

books and pontificate too often. Love really does happen, and it happens when

Christians hang out with Jesus. In fact, the solution to most of the problems

we have with ourselves and with the world is to just go to Jesus and then not

leave until we’ve been loved. You’ll know, and they will too.

Q: How do we, as Christians, create questions in the

minds of unbelievers?

By doing the

unexpected. Martin Luther, for instance, gave some advice to a pastor friend

that was helpful. He pointed out that certain things were very irritating to

the very religious. He told his friend to find out what they were and then to

“do them.” I’m sure Luther would put some boundaries on that advice, but not

much. Our subculture has created a list of laws that would make an Orthodox

rabbi blush. There are so many “do’s” and “don’ts” that it’s intimidating. The

truth is most of those are not from the God of the Bible but from our own

efforts to be better and better every day and in every way. Transformation is

no longer being increasingly like Jesus but becoming increasingly more

religious.

So, to create

questions, Christians need to break out of that mold, push the line and shock

the world. We do that by loving the wrong people, going to the wrong places,

quoting the wrong writers and cutting slack for the unrepentant, and it goes on

and on. I have a friend who has Bible studies for strippers and another friend

who is straight who goes to gay bars to hang out. You wouldn’t believe the

questions.

I think it’s

important for Christians to figure out where in their own lives the comfort

zone is . . . and then to go one step further.

Comments